Today, in my grubby sweatpants, cleaning the house, I got a call from my dad. He rarely calls, funny, really, since he used to say the same about his own father. And yet when he does call, or when I call him, there’s always a flicker of joy, of readiness. This time, he was in an antique mall in North Carolina, with my mom, my sister, and my sister’s family. They all live in the same town in NC.

“Did you get the pictures?” he asked. I hadn’t. He stepped outside to resend them, and soon they came through: a trunk full of deer antlers, and then my mom holding one up so I could see the size.

A few weeks earlier, during one of their (once or twice a year) visits to Philadelphia where I live, I had taken them to a nearby town. We stopped for lunch at a little café with a plant-and-knickknack shop next door. I kept appreciating the many antlers on display, hoping to find a price tag. There were none, as they weren’t for sale. The owner having a nack for finding them antique shopping, the woman working told me. I had been looking for one to hang in my bathroom, above a deer print my son gave me. But everywhere I found them they were more an artefact of a shop owner’s affinity for them than one for sale.

This search for antlers would’ve been a strange request coming from my younger self. I was once fiercely anti-hunting, anti-meat, anti-taxidermy. My grandfather had a hunting room lined with mounted deer heads and a rug made from a full bear skin. The bear was actually more than a skin: it had a head and paws, with teeth you could touch. It’s rubbery tongue was removable and my sister and I would play with it. My grandmother did not love it when we placed it in locations other than in the bear’s mouth. Some of the mounted antlers in that room had things hanging on them. Several had head pieces made of flattened snake skins, rattles and all, coiled into threatening headbands—snake head positioned to strike. I wish i had that now! As a child, I loved it. As a teenager, I found it grotesque.

But age softens us. And something about the antlers—their shape, their memory, their echo of the woods I live so far from now, draws me in. I want to surround myself with reminders of something that I can’t quite define. I don’t want to hunt them though, thus, this the desire to find them tucked in a dusty antique shop’s corner.

Now, weeks after that outing, my dad was calling to tell me what they’d found at an antique fair. My whole family was there, my mom, my sister, her family-- celebrating my sister’s birthday, doing the kind of wandering and shopping that makes up a day together. It’s the kind of gathering I often miss, living far away.

At forty-something, it’s become less common to receive gifts from my parents. Maybe that’s what made the call feel so tender. My dad was excited, genuinely wanting to know if I liked the antlers, and which ones I preferred. It was a gift. Not just the object, but the act of remembering. Both of my parents reaching out to see if they had finally found what they knew I had been looking for.

In my family, gifting has always been one of the clearest ways we say “I love you.” It showed up in the form of food too, your favorite meal when you came home from camp, the dish you requested on your birthday or for Mother’s Day. Every summer, when I came back from the annual youth group trip to Mexico, my mom would make homemade pimento cheese and set out a bowl of fresh cherries.

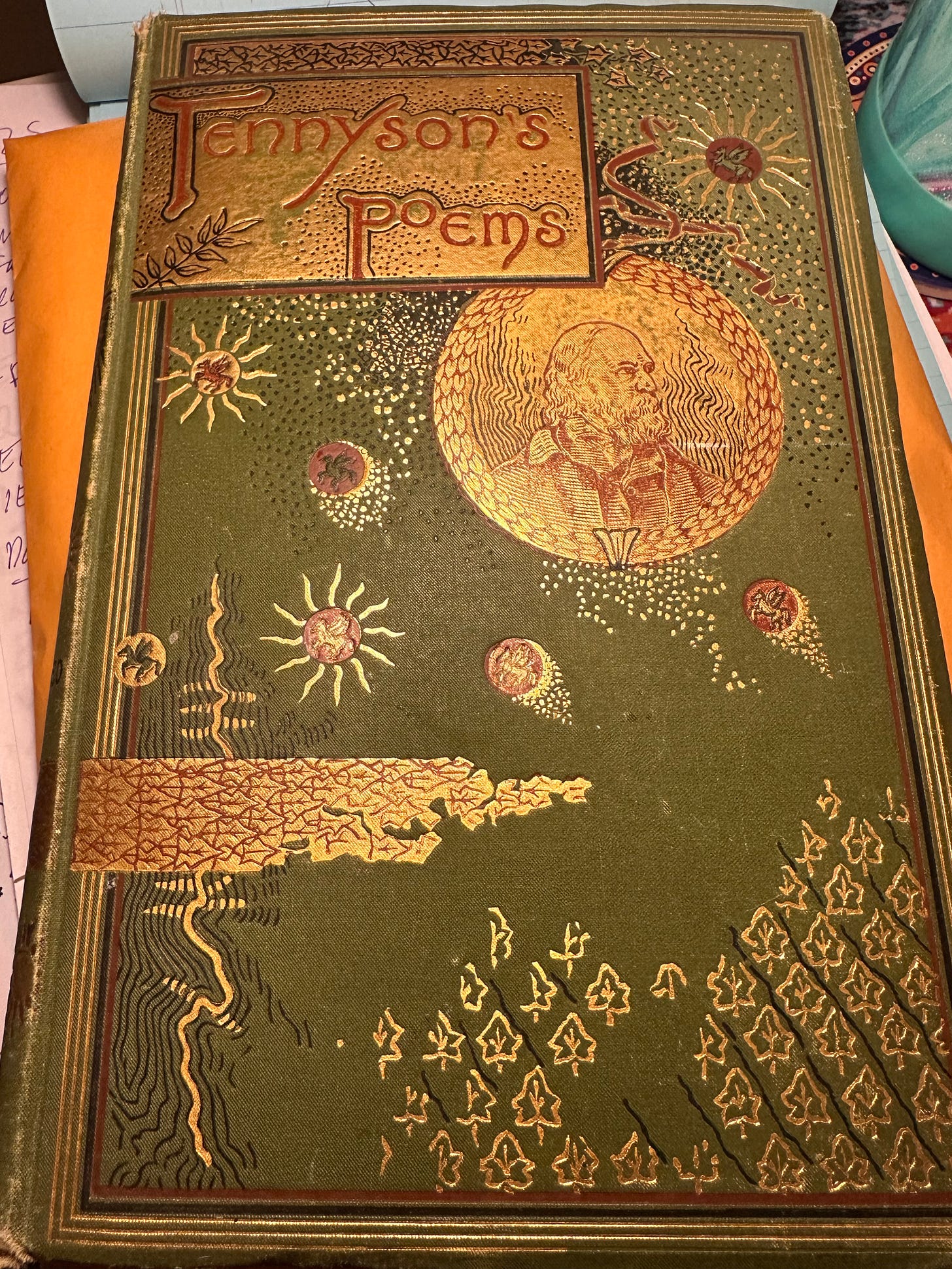

When I was in college, my dad once mailed me an antique edition of Tennyson’s poems. I loved poetry deeply, and he was not a reader, so this beautiful version of a collection of poems meant a lot. Another time, he sent a thick black hardcover: Thoreau: Collected Essays and Poems. I had loved my middle school discovery of Thoraua’s writings, and had spent hours sitting in the woods behind our home writing in my journal and reading his essays.

Inside the front cover, in black Sharpie, he had written a note in his signature handwriting—capital letters intermixed with lowercase, a few little rounded cursive ones. The date read "7/3/01" and it was addressed to me as:

T-R-A-C-i — the T, the R, the A, and the C capitalized, and the I distinctly lowercase, with the dot above it carefully marked.

And then, in his words:

“A special book for a very special daughter, just a little something to let you know how proud I am of you and all the things you have accomplished in your life. Love you always,”

(Signed)

D-A-D — all capital letters, underlined.

My dad is not a man of many words, not emotionally effusive. These gifts held meaning.

He’s often piddling around the house, disappearing into tasks. But if you catch him early in the morning, or alone at the table, sometimes he shares stories. And one he told me again and again was about how moving away from East Tennessee, his home, his family, was one of the best things he ever did.

“Traci,” he said more than once, “it’s good to move; you will just see things differently.”

So I did. Maybe not in the way he meant and not fully consciously because of this story. But I moved, first to Western NC for college, then to Maine, then Mexico, then the Czech Republic, Germany, Western Massachusetts, Hudson NY, and finally, Philadelphia. I made a life elsewhere, farther than he ever had. And now, as a divorced mom rooted in a city that became mine almost accidentally, I’m tethered by the needs of children, shaped by my own version of leaving and staying. By my own multiple versions of home.

It’s not always easy to explain what pulls us toward or away from our families. Why we leave, or what keeps us rooted. I’ve thought about that a lot lately. About how our departures aren’t always rejections, and our staying isn’t always belonging.

There’s a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated (in this version) by Robert Bly, that stays with me:

Sometimes a man stands up during supper

and walks outdoors, and keeps on walking,

because of a church that stands somewhere in the East.And his children say blessings on him as if he were dead.

And another man, who remains inside his own house,

stays there, inside the dishes and in the glasses,

so that his children have to go far out into the world

toward that same church, which he forgot.

I don’t know if my dad was the man who walked or the one who stayed. I don’t know if I am. We both moved. We both carry the longing of that church, whatever it stands for, inside us. (Maybe all of us do?) What I do know is that families shape the direction of our journeys, whether we know it or not. They send us off with stories and silences, with blessings and contradictions.

And so when I finally hang that antler above the deer print in my bathroom, it will be more than decoration. It will be a relic of remembering. A gift of love. A quiet signal between my parents and me, across years, across silence, across all the ways we’ve both stayed and gone.It will be a gift, yes, but also a tether, keeping close what time and distance tend to loosen.

REFERENCES

Hass, R. (1993). Introduction. In R. M. Rilke, Selected poems of Rainer Maria Rilke (R. Bly, Trans., pp. xi–xliv). Vintage.

Tennyson, A. (1884). The complete poetical works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, poet laureate (Illustrated ed.). Harper and Brothers.

Thoreau, H. D. (2001). Collected essays and poems. Library of America.

I love this Traci. 💞